Earlier this year I created a series of posts about making wine using the cubicontainer technique that relies on a single container, rather than using two containers for primary and secondary fermentation. This approach requires that you use juice, and not raw fruit/vegetables, as the source for the wine. Most people think that you can make juice only from a raw source, such as crushing grapes. However, wine makers know that you can use both raw and cooked juice. This post shows how to work with raw juice—pears in this case. If you haven’t read the wine making series of posts, you can find them at:

- Wine Making – Day 1

- Wine Making – Unsticking a Batch

- Wine Making – Day 10

- Making Wine – Day 23

- Making Wine – Day 28

- Making Wine – Day 31

When working with any fruit for raw juice, you need to pick the fruit at the peak of ripeness. In the case of pears, this means smelling the fruit for the distinctive pear odor. The fruit should still be firm, but crush easily in the hand. Taste the fruit and you should smell a strong pear odor, along with a high sugar content. Check the inside for an off white appearance. If the fruit seems starchy, the inside has yellowed or browned a bit, or seems mushy to the touch, it’s overripe and won’t make good wine. Likewise, if the fruit is still greenish in color, seems a bit too firm, or lacks the strong pear odor, it isn’t ripe enough. Every fruit has its peak time for picking that typically last one or two days. That’s right—you must check the fruit absolutely every day or you’ll miss the perfect time to pick it.

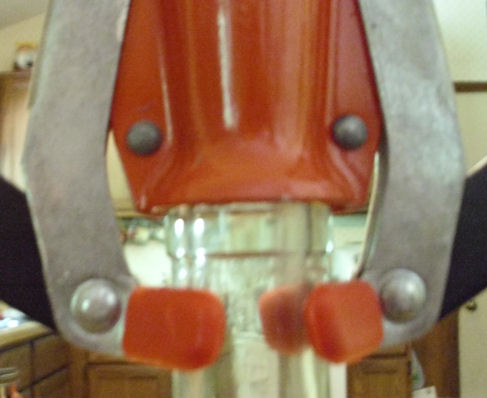

In order to create the juice, you begin by running the raw pears through a Victorio Strainer. You need to be absolutely certain that the pears are ready for use in wine. Pears that aren’t ripe could damage your strainer. Normally, the juice turns a bit brown as you strain it due to oxidation and the presence of bacteria. In this case, you’ll prevent that from occurring by adding a campden tablet to the output of the Victorio Strainer and stirring the juice from time-to-time as you strain the juice. The result should be a slightly greenish yellow juice as shown here.

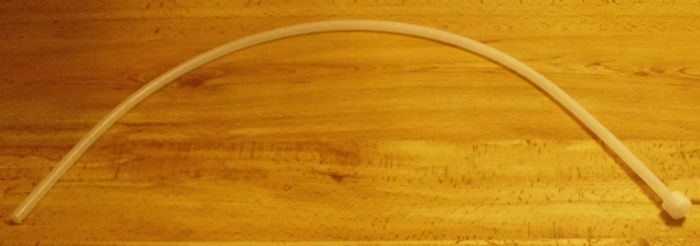

However, this juice isn’t ready for wine making yet. It still contains a substantial amount of pulp. You need to make at least 2 quarts of strained pear juice to obtain 1 quart of juice ready for wine making. The next step is to place a jelly bag over a 1 quart measuring cup like this:

Pour as much of the strained juice into the jelly bag as possible. Now you’ll squeeze the bag to separate the pulp from the juice like this:

Once you have a quart of juice, you can use it immediately to make wine or freeze it for later use. A quart of pear juice will make one gallon of wine using the wine making techniques I discussed earlier. If you decide to freeze the juice, make absolutely certain that you mark it for wine use only because the juice already has the campden tablet in it.

This same technique works fine for any fruit that gets soft enough when ripe to put through the Victorio Strainer. For example, it works great with berries. However, I haven’t ever gotten this technique to work properly with apples—most apples are still too crisp when picked to get through the Victorio Strainer successfully. Apple wine requires the use of a cider press or the cooked juice method. Other fruits, such as rhubarb, require the cooked juice method. You can use this technique for some vegetables as well. This is the technique I use to make tomato wine. If you want to work with a harder vegetable, such as beets, then you need to use the cooked juice method. (I’ll describe the cooked juice method in a future post.) Let me know if you have any questions about this technique at [email protected].