This is an update of a post that originally appeared on June 30, 2011.

Some examples work well across multiple editions of my book with slight modifications, so if you have the third edition of my book and this code looks familiar, it probably is with small changes. The example in question in this case now appears in Book I Chapter 7 of C++ All-In-One for Dummies, 4th Edition. The example shown in Listings 7-6, 7-7, and 7-8 describes how to declare a global int variable using extern and one reader wanted to extend this example to the string type. The reader had tried several times, but kept getting the following error message (in fact, you can find this same error in Code::Blocks 8.02 and 10.05 and the update in this post works with both versions):

error: 'string' does not name a typeI’m assuming that you’ve already read the discussion about this example (be sure you read the entire section from pages 183 to 185). Creating a fix for this problem isn’t hard, but providing some example code will make things easier to understand. The first issue is to include the required support in main.cpp (shown in Listing 7-6). Here’s an updated version that includes an entry for a string variable named CheeseburgerType.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include "sharealike.h"

using namespace std;

int main()

{

DoubleCheeseburgers = 20;

CheeseburgerType = "Deluxe";

EatAtJoes();

return 0;

}As you can see, you must provide #include <string> and then set CheeseburgerType to a value, which is "Deluxe" in this case. Otherwise, the example works precisely the same as before.

Let’s look at sharealike.h next (Listing 7-7). The following code changes are essential or the example will never work.

#ifndef SHAREALIKE_H_INCLUDED

#define SHAREALIKE_H_INCLUDED

using namespace std;

extern int DoubleCheeseburgers;

extern string CheeseburgerType;

void EatAtJoes();

#endif // SHAREALIKE_H_INCLUDEDNotice the inclusion of using namespace std;. The example will fail to compile without this statement added unless you specify the namespace as part of the type declaration. Once you define this addition, you can create the extern string CheeseburgerType; declaration. Of course, if string were part of another namespace, you’d use that namespace instead.

The final part of the puzzle is to create the required implementation. This part appears in sharealike.cpp (Listing 7-8). Here’s the final piece of the example:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include "sharealike.h"

using namespace std;

int DoubleCheeseburgers;

string CheeseburgerType;

void EatAtJoes() {

cout << "How many cheeseburgers today?" << endl;

cout << DoubleCheeseburgers << " " << CheeseburgerType << endl;

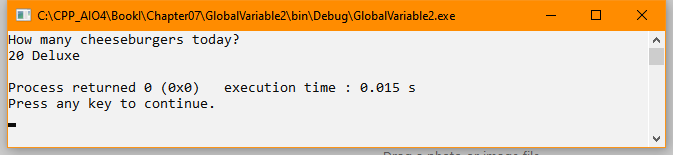

}As with main.cpp, you must add the appropriate #include. In addition, this part of the example updates EatAtJoes() to include CheeseburgerType in the output. When you run this example, you’ll now see a cheeseburger type in the output as shown here:

Are there any questions on this extension? Please let me know at [email protected]. You can download the updated version of the code as GlobalVariable2 here: