There are cases where it’s very tough to figure out the correct presentation of material in a book, which is made more difficult by some readers preferring one presentation and other readers another. It comes down to how people learn in many cases. Visual learners prefer screenshots, abstract learners prefer text. Of course, there are all sorts of learners between these two extremes. So, what seems like a simple question can become quite complex.

The question at hand is whether to present screenshots of an IDE in a book with the associated example code and its output. The problem is that vendors now assume that developers have very large displays and so have made use of all of that extra screen real estate. In addition, book publishers don’t want books where a single image consumes an entire page. The result is that it’s very hard to get a screenshot where the text is completely readable. It can be done, but the text will generally still be smaller than the print in the book. Older readers complain that they need a magnifying glass to see the text at all.

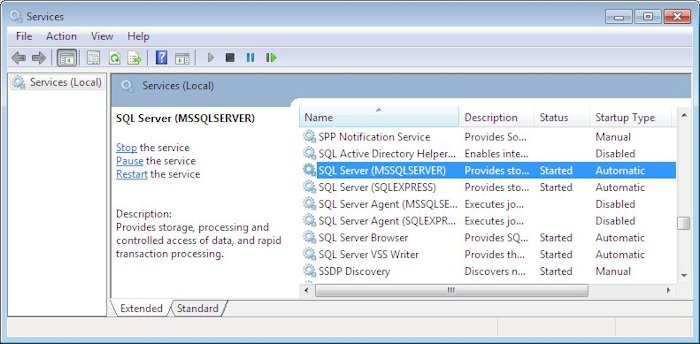

However, there are benefits to using screenshots. The most important benefit is that, even if the text isn’t completely readable, visual learners can see what their IDE should look like as they follow the progress of procedures in the book. This feedback lets the visual learner know that they are doing things correctly and are getting the correct result. Another benefit is that an example tends to stay in one piece. The graphical output of an example doesn’t end up several pages away from the source code that produces it. Sometimes, textual output is wider than the page will allow using the normal font size. So, the options are to print the output in the book at the normal font size, but in a truncated form, which means that it’s no longer complete. A screenshot can show the complete textual output, but at a smaller font. For beginner readers, the second form, while not optimal, is preferred because truncating the output produces questions in the reader’s mind.

So, how do you feel about IDE screenshots in books? Are they more helpful or more confusing? Part of the reason for posts like this is to get your opinion and discover more about you as a reader. Obviously, a book author wants to use the communication techniques that work best overall for everyone, book space often not allowing for the investigation of every presentation alternative. Let me know your thoughts at [email protected].