One of the centerpieces of self-sufficiency is, surprisingly enough, sharing and swapping food with neighbors. Yes, it’s possible to grow everything you need yourself, but absolutely everyone has a bad year in something. In addition, your soil and gardening techniques may produce copious quantities of one item, but prove dangerous, or even fatal, to other items. Your neighbors will have similar luck with other items. Consequently, swapping items between neighbors is one of the hallmarks of a self-sufficient community. The community as a whole benefits in such a situation because everyone ends up with a greater variety of food to eat. So, while you can grow what you need, you’ll eat better when you swap with someone else.

It isn’t just the garden though. Just about everything is swapped at times. One person may have an abundance of chickens and trade a chicken or two for some beef. These swaps aren’t done on a strict accounting system. People tend not to get too caught up on the price of the food—they’re more interested in exchanging something they have in excess for something they need. Of course, no one would swap an entire cow for just one chicken either ![]() . While the swaps aren’t strictly fair, they’re reasonably so—no one tries to take advantage of someone else (otherwise, the community as a whole would stop swapping with them).

. While the swaps aren’t strictly fair, they’re reasonably so—no one tries to take advantage of someone else (otherwise, the community as a whole would stop swapping with them).

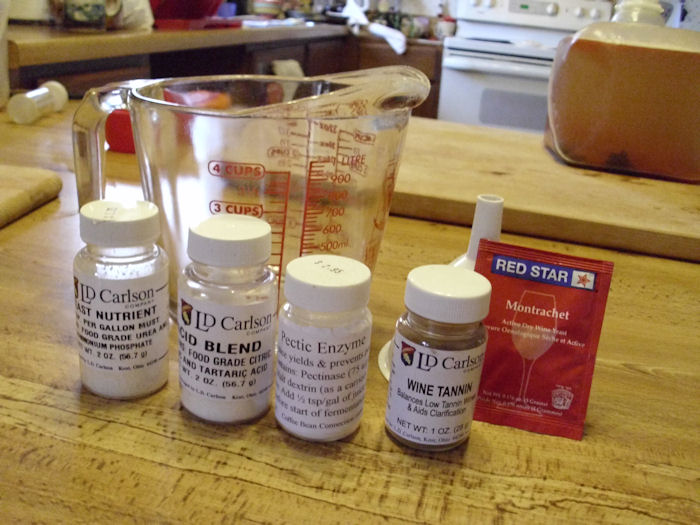

There are times when people simply share food, which is where the country ethic comes into play. We’ve shared wine, soap, or cookies with other people simply because we think they’re nice people and want them to enjoy something we’ve made. There is no other motive behind the act, other than seeing the smile on the other person’s face. It makes us feel good to see how others react when we do something nice for them—acts of kindness are their own reward.

People have also shared with us. One winter we were extremely low on wood and I wasn’t able to get out and cut any. Our neighbors sent three cords of wood our way—an extreme act of kindness that we’ll never forget. We recently received a nice buck from some friends for nothing more than a smile. It isn’t often that you can fill your freezer with venison because of the kindness of someone else. The 65 pounds of meat is nice, being able to use the tenderloin for Christmas dinner is even nicer. I’ll make some lovely venison medallions (with wine we’ve made no less). It will be an extremely special Christmas—one we’ll never forget.

Our swapping and sharing often extends outside our local village. Other good friends recently sent us a decadent cake that we’ll share with family and friends here. We’ll send a fruitcake their way later this week. I wish that our friends could have seen the smile on our faces when we received the cake—perhaps they felt the warmth of our feelings from afar (and certainly we’ve thanked them for their fine gift).

If you choose to become self-sufficient, don’t get the idea that you’re an island. No one is separate from the entire world. The more self-sufficient you become, the more you realize that the self-sufficiency of the community in which you live is important. It doesn’t matter if you live in the country, as we do, or in the city. The need to depend on others and also experience the joy of giving to those in need is possibly the best part of being self-sufficient.

Does your community swap and share? How are you experiencing the kindness of others during this holiday season? Have you done something kind, something totally unexpected for someone else? Let me know at [email protected].